| Histology

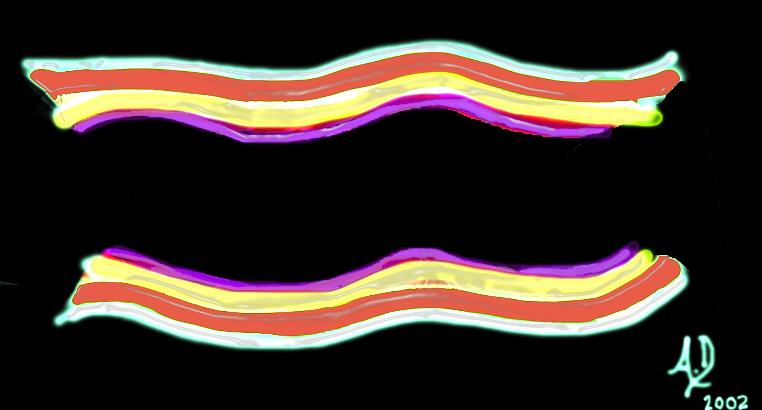

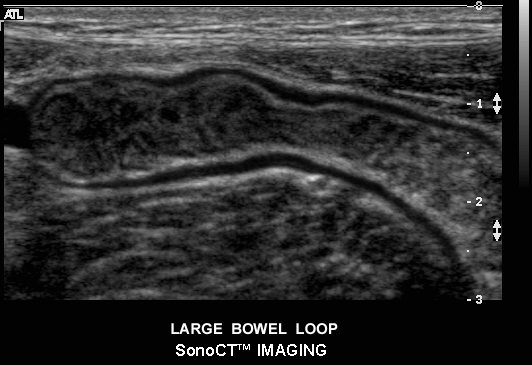

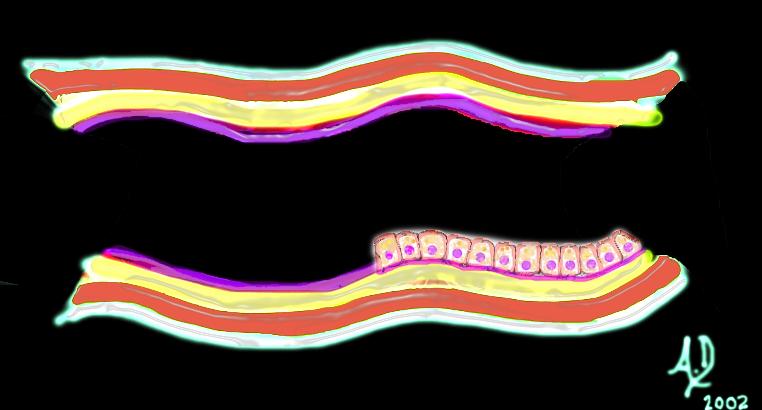

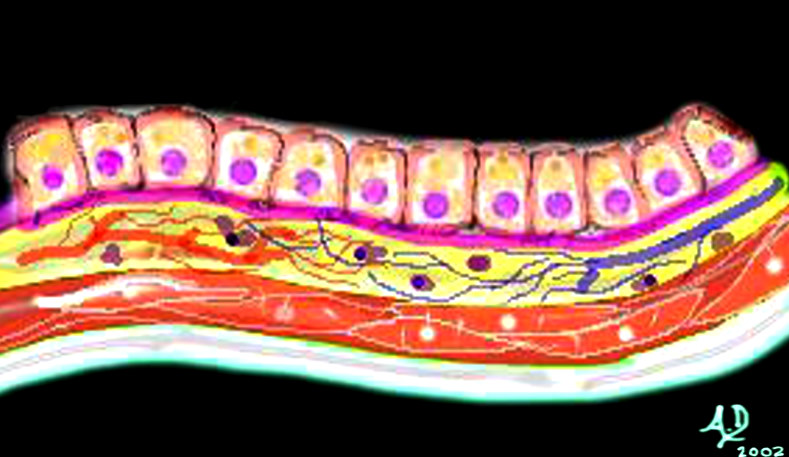

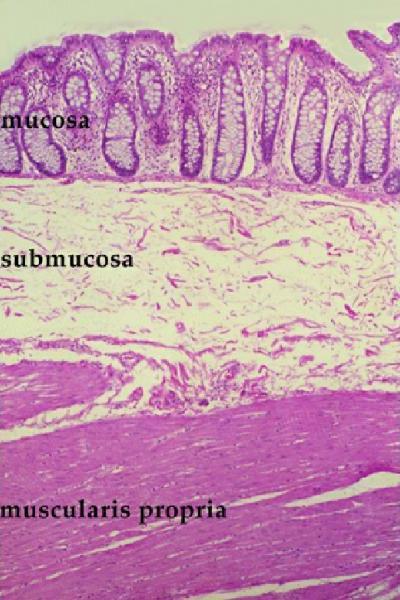

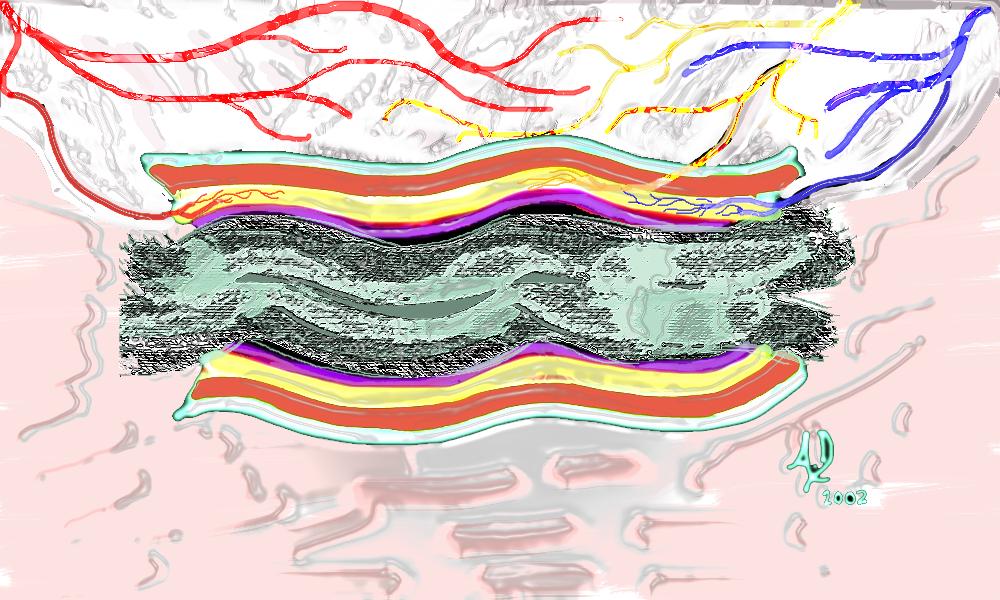

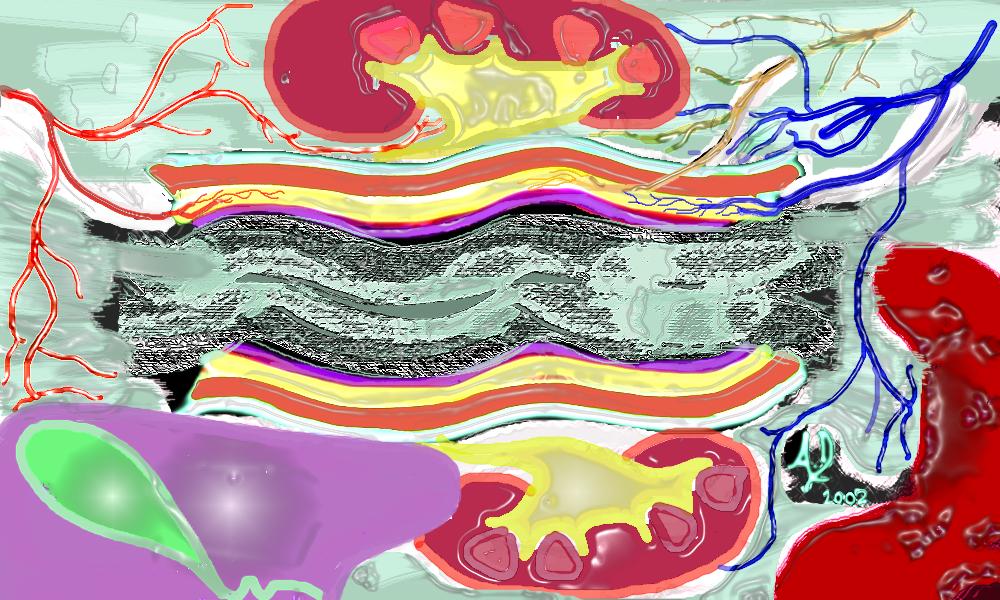

Let us examine the histological makeup of the colon first in the context of other tubular systems and then review its makeup with a focus on how it functions. Like many other tubes in the body its wall has 4 layers. The inner layer that lines the lumen is called the mucosa which rests on its basement membrane. The mucosa consists of a single layer of rectangular cells and the layer is called an epithelium. Because of the rectangular shape of the cells they are called columnar cells and so the layer is called a columnar epithelium. The second layer is the submucosa which contains blood vessels, lymphatics, nerves and loose connective tissue. The third layer is the muscular layer called the muscularis and the fourth layer is called the serosa or adventitia which acts as a protective outer “skin” for the colon. This layer is called a serosa when it is surrounded by peritoneum (transverse colon and sigmoid colon) and called an adventitia when it is retroperitoneal. (ascending colon, descending colon and part of the rectum)

The submucosa contains the vital lifelines including the terminal branches of the arteries, the capillary network, the smallest and earliest venous branches and the lymphatics. There are nerve endings in the submucosa as well as the muscular layer. Circulating white cells that perform the vital local defense functions police the submucosa for potentially harmful organisms and substances. The muscularis contains spindle shaped smooth muscle cells while the serosa and adventitia consist of relatively strong connective tissue, and in the case of the serosa a layer of epithelial cells derived from the peritoneal lining.

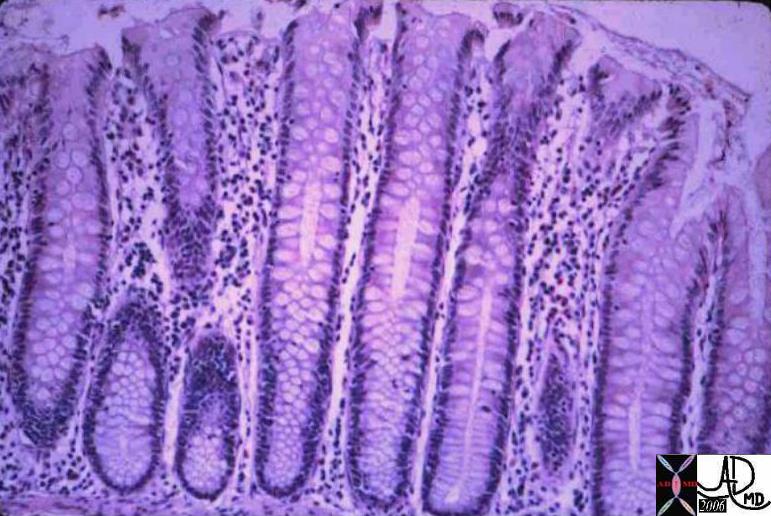

In order to optimize water absorption the mucosa of the large bowel is thrown into innumerable folds creating the crypts of Lieberkuhn which look like epithelial lined test tubes. Unlike the small bowel the mucosa does not contain villous projections, but rather these mucosal infolds called crypts which contain mucus secreting and water absorbing cells. By creating tightly packed infoldings, the surface of the colon is increased significantly. Macroscopically the mucosal surface of the colon is mostly smooth except for folds called the plicae circulares which are formed by the pleating effect of the taenia coli.

The wall of the colon requires a very substantial vascular supply and effective nerve and lymphatic system in order to coordinate its function with other physiological events occurring within the gastrointestinal system specifically and within the body at large. The neural, lymphatic, and vascular channels enter through supporting mesentery and penetrate the wall (just like the cable systems, water systems, electrical and sewerage enter and leave our homes). These penetrations produce weakening of the wall and remain the potential site for diverticuli to develop. The vessels terminate in the submucosa.

The mucosa and wall of the bowel are not isolated structures. John Donne a clergyman and poet from the renaissance period stated that “… No man is an island …” In the same way no organ is an island Each is connected and dependant on the other organs and the colon and its substructures are no different. It is not surprising therefore that disease of the colon for example is associated with disease in other parts of the body. The association of ulcerative colitis and sclerosing cholangitis is a prime example. The psyche and the bowel are also intimately related. Acute anxiety is notorious for inducing diarrhea.

The proximal large bowel is presented with the sludge like by products of small bowel digestion consisting of mostly water, and undigested complex carbohydrates. Colonic mucosa absorbs most of the water and together with churning action and bacterial digestion, the nature of the sludgy semi liquid stool is transformed into more solid and compacted stool.

|

The 4 basic layers of the colon

The 4 basic layers of the colon Ultrasound of normal large bowel

Ultrasound of normal large bowel The mucosa

The mucosa

An artistic rendition of columnar epithelium

An artistic rendition of columnar epithelium Mucosa submucosa, muscularis and serosa (adventitia)

Mucosa submucosa, muscularis and serosa (adventitia) Histology of the mucosa, submucosa and muscularis

Histology of the mucosa, submucosa and muscularis Normal Colonic Mucosa

Normal Colonic Mucosa The submucosa

The submucosa Vascular entry into the transverse colon

Vascular entry into the transverse colon Colonic connections

Colonic connections